OFF TO AFRICA

Some nine years after deciding that I wanted to work in agriculture in what was then termed “the developing world”, in the early summer of 1968, I found myself both completing my doctoral thesis at Wye College and preparing to travel to Africa to take the post of lecturer in crop production at the Swaziland Agricultural College. I was advised by my employer that I needed to ship out a number of items with which to fit out my house, which led me to a large shop in Piccadilly that had for decades served those going out to serve in the colonies and could still provide me with a pith helmet and a portable, folding canvas bath for when I went on trek! In order to purchase what I required, including a sturdy suitcase and a trunk, I would need around £75. This is a ridiculously small amount of money today (currently equivalent to £1,750) but at the time my annual grant to cover all my living costs (accommodation, food, clothing and travel) was only £500 so £75 was 15% of my annual grant. As I could only muster £25 from my savings, I hitched a lift into Ashford to see the manager of the National Provincial Bank (which merged with the Westminster Bank to become the National Westminster Bank – later Natwest) to ask for a loan of £50. Despite my letter of appointment being from a British Government parastatal, with a not-to-be-sniffed at salary of £1,200 a year, (£27,000 today) my request was turned down out of hand.

Hitching back to college I was picked up, serendipitously, by the wife of my Prof in her smart blue Hillman Imp and during the few minutes of travel she extracted from me my forlorn story of the rejected loan and commiserated. The next day, I was called in to see the Prof – a dour Scot of few words – who said that he understood that I had a problem. Perplexed, and assuming that my thesis was in trouble, I shuffled and asked for clarification – to which he replied “would £100 meet your needs?” Bless him, after hearing my story from his wife he wrote me a cheque for £100, unsecured “to be paid back when I had the funds”.

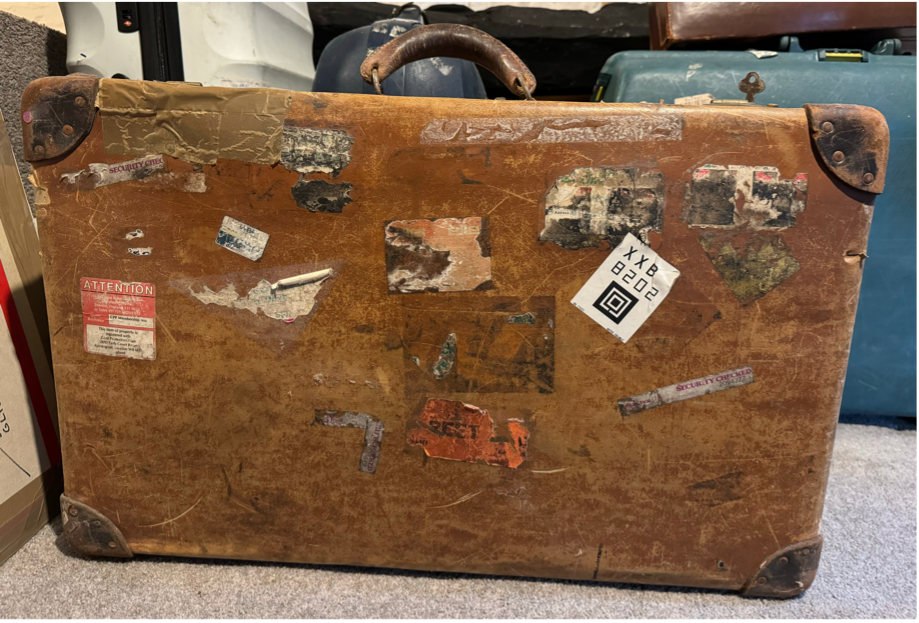

Having never been to Africa before, packing was a novel experience – both for the long term (i.e. the next two years in Swaziland) and in the short term (travelling through Uganda, Kenya and South Africa to Swaziland). Central to the latter was my suitcase. With a steel frame and a moulded exterior, it was impenetrable without the key (itself a complex one). But it weighed in empty at around five kilogrammes and, crucially, was from a time long before the idea of adding wheels to suitcases had emerged. It was heavy when empty and much, much heavier when packed.

Thus in funds, with household items purchased and safely with the shipping company and with my suitcase in tow, I arrived at Heathrow in early September to take a plane – a British Overseas Airways Corporation VC10 – to Uganda. Why Uganda? Conscious that I had absolutely no experience of Africa or of agriculture in Africa, and that I was to be a lecturer in crop production (in Africa), the College Principal thought that it would be a good idea for me to spend a couple of days at Egerton College – a leading agricultural educational institution in Kenya - with John Acland, the author of the authoritative book East African Crops. Wanting to get a little experience of Africa before meeting this high-profile gentleman, I approached a friend - who had left Wye the year before and was now established in Uganda running a dairy project not far from the international airport at Entebbe. I asked if I could come and see her on my way to Kenya.

Back in the 1960s, communications were slow – although we didn’t think so at the time. The main form of communication was by letter – airmail in the case of Africa. In those days the postal service, not only in UK but also across the world, was very efficient and reliable. In the 1960s my grandfather could post a letter to someone in his hometown at 0900 on any weekday and know that it would be delivered the same day. My communication with Wendy in Entebbe would therefore be by airmail. A reply would be expected within a week or so. International telephone calls were prohibitively expensive and any urgent communication would be sent by a brief telegram – the price increasing with each word.

And so I arrived at Entebbe airport in the late afternoon of September, some eight years before the infamous and week-long highjacking of an Air France Airbus 300 with 248 passengers on board by two members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – which played out on international television. These were my first steps on African soil - in the warm and humid atmosphere looking over Lake Entebbe.

Wendy, and her partner, whose surname is sadly lost amongst my ageing grey cells, were managing a dairy project on the shores of Lake Entebbe. They had been provided with a small bungalow whose mosquito-proofed veranda looked out over these same shores and on which we sat and caught up on the world, drinking a cold beer and watching the deep orange sun slide over the horizon, its reflection shimmering on the placid surface of the lake.

They had arranged a bed for me on the veranda, perhaps so that I could experience first-hand the sounds of the African night. I climbed into bed and fell quickly asleep after a long and exciting day. I woke to the sound of rain peppering down on the tin roof, to flashes of lightening and rumbles of thunder. The rain was accompanied by a strong wind. The temperature dropped. The cacophony of light and sound grew nearer and nearer until it seemed that the eye of the storm was enveloping the house. I was quite terrified. But sought to console myself that – after all - this was what happened Africa. So I lay there – scared out of my mind - whilst believing that this was par for the course.

Next morning my hosts emerged. “Wow” said Wendy “we’ve never experienced anything like that before! Did you stay out here all night? We’d thought you would have come inside!”. And so passed my first night in Africa.

After couple of days observing what they were doing I got ready to travel to Kenya on an East African Airways flight. It was due to leave at 0830 with a check-in at 0700 – air travel being less of a scrum than it is now. Around 0630 I heard the roar of a plane taking off from the nearby airport and climbing over the bungalow. It was only when I arrived at the airport that I realised that the sound I had heard was my flight taking off. They had decided to leave early, for reasons which were never explained. By the time I realised it my host had gone. Mobile phones were not even a dream and so I found myself alone at the airport, unable to communicate with neither my Ugandan nor my Kenyan host.

After some deep breathing I took stock of the options – of which it transpired there was only one. There was another flight to Nairobi that evening. My ticket was transferable. I could hang around the airport and wait. And so I found myself sitting outside on the balcony overlooking the area where the arriving planes – of which there were few in those days – parked and passengers emerged down the steps which had been rolled up to the plane by hand. As I had my guitar with me, carried in a soft leather case which my Mum had made, I sat and strummed and quietly sang and engaged in conversation with passers-by and through these conversations learnt a little more about travelling in Africa.

In the late afternoon my plane duly arrived and we boarded. We took off and landed in Nairobi around an hour later. It was already getting dark. Being on the Equator, Nairobi’s days are roughly the same length year-round – with the sun rising around 0630 and setting some twelve hours later. Unlike Entebbe, where I had been met by a friendly face from my college days, I was alone and needed to find somewhere to stay overnight. I hailed a taxi and asked if he could recommend an inexpensive hotel. He did and he took me to a small hotel where, I realise in retrospect, he was probably given a commission for bringing them my business.

I was ushered into a small room and immediately fell asleep – only to be woken repeatedly by soft knocks on the door and various female voices whispering “Hello Mister, you want nice time?” It was only in the morning that I realised that my taxi driver had brought me to “short-time” hotel where I could meet Nairobi’s good-time girls.

Having survived the night, I needed to get to Egerton College on public transport both promptly and on a budget. I learnt that I needed to take “a Matatu” from Nairobi to Nakuru and then get a bus from there to the college. The 1968 Matatu in Kenya was quite different from the brightly coloured mini buses that can be found across Africa. In 1968 in Kenya the Matatu was a Peugeot 404 station wagon with the luggage compartment replaced with a third rows of seats and with strengthened suspension to carry its load of nine passengers plus their luggage, which now had to be strapped to the roof.

At that early post-colonial time there were three makes of vehicle that dominated Africa’s roads. The Peugeot 404 was by far the most popular – not only for its design (by the Italian Pinafarina sporting sharp fins at both front and rear) but also because it was fast and its rugged suspension smoothed out the endless bumps and ruts on the gravel roads. The Mercedes, also fast and rugged, was favoured by the few with money to spare and an ego to display. Whilst the Land Rover, in those days built like a Meccano set in which every part could be removed at the turn of a spanner and which was extraordinarily uncomfortable, dominated in the rural areas. Japanese vehicles had yet to arrive at scale in the African market. I can remember that when the first Japanese double-cab pickups arrived in South African I wrote to a British car manufacturer highlighting their increasing popularity and encouraging them to follow suit - only to be told that it was a passing fad. The same was true with the Land Rover which failed to respond to the challenge of the Toyota Land Cruiser – resulting in the increasingly popular phrase….”A Land Rover will be get you there - but a Land Cruiser will get you back!”

To get a Matatu to take me to Nakuru involved a trip to a taxi park where they were lined up to absorb the awaiting passengers, each one roaring off as soon as it was full – a driver and two passengers in the front and two rows each of three passengers behind… the luggage on the roof. I found myself in the middle of the second row, squeezed between two large Kenyans. Seat belts seemed to be an optional extra.

We set off on the gravelled roads. Judging by his stretched ear lobes the driver was a Masai. Whether motivated by getting back to his cattle, or by filling his car with another eight passengers for the return journey, his foot was permanently flat on the floor – as near to 80 mph as possible even when hurtling downhill to a level crossing in order to beat the steam train slowly approaching to our right. After two hours, with eyes frequently closed and fists clenched, we arrived at Nakuru where I retrieved my heavy suitcase and began asking how to get to Egerton College on public transport. The answer was on a small, green, elderly and unmarked bus which seemed to be all metal seats and open windows and which was parked at the side of the road on a hill. I climbed in with my suitcase, the first passenger. After some time, the driver arrived and I asked him if he could drop me at Egerton College. He agreed. Sitting on the metal driving seat, which was mounted on a heavy spring to provide some comfort on the gravelled road, he took hold of the knob at the top of the long, curved gear stick and put it into gear. Reverse gear. Releasing the brake, we began to run backwards down the hill for a few seconds before he released the clutch. The bus shuddered and the engine spluttered into life – the battery was clearly flat - my first of many such encounters in Africa.

After about half an hour the bus slowed down, seemingly in the middle of nowhere. The driver pointed into the middle distance to the left and said “Egerton College”. I got out and watched the bus drive off. It was mid-afternoon. I had not eaten since breakfast. It was very hot. All I could see was a dirt road going off to the left with a small sign saying Egerton College. I set off in the hot sun. My case was heavy - increasingly so as I realised there was no sign of the college. It was more than half an hour later, trudging along the dusty road that I got first sight of the college – spread out in its colonial splendour – and another 15 minutes before I found the house of my host. He opened the door to see my young self, standing there dusty and red-faced from the sun and from the exertion of carrying my case. “Where have you been?” he said “I was expecting you yesterday” clearly displeased at my arriving a day late - his having set time aside for me the previous day. My excuses must have seemed hollow. It was not a good start.

We had dinner together and he then explained that as there was no spare room in his house, I would be staying in the school building nearby where a bed had been installed. He also told me that everyone on the campus was on edge at the moment as a local farmer had recently been murdered and no culprit had been found. In the light of this my host told me that he had a gun by his bedside. I was dropped off at the schoolhouse. It was dark. I was alone. I went to lock the door. There was no lock. I found a wooden chair and rammed it against the doorknob in the wild belief that this would prevent someone entering the building. Not surprisingly I did not sleep well and longed to be sleeping on a veranda in the midst of a mighty storm. The night passed and after breakfast I got out my notebook and learnt all I could absorb.

Going South. After a couple of days, my head full of possibilities and lessons learned, I was dropped in Nakuru for another heart-stopping drive in a Matatu back to Nairobi. Staying overnight in a more salubrious hotel, next morning I took a taxi to the airport to board another VC10 down to Johannesburg. The airport was my first exposure to apartheid – to whites-only and non-whites-only queues, toilets and cafes. As I changed my travellers’ cheque to Rands and made the transit to the gate for my flight to Swaziland there was little time to take this all in.

We queued at the gate and boarded the bus out to the waiting plane. It was a Douglas DC3 (the Dakota) – an early progenitor of the DC8 narrow-bodied, long-range jet that, together with the Boeing 707, dominated the skies until the emergence of the wide-bodied Boeing 747 (Jumbo Jet) and the DC10. To modern eyes the Douglas DC-3 looks rather odd, with two large wheels at the front and one small one at the rear, such that when stationery it appears to be sitting on its haunches. It reminded me of the even older Avro Anson, in which as sixth formers in the Air Training Corps, we were required to do endless “circles and bumps”.

Having entered the plane through the door at the rear, passengers walk “uphill” to find their seats. It is only when the plane takes off that the frame become horizontal. It was one of the most successful civil aircraft ever built [1]. Its innovations included retractable landing gear, wing flaps, variable-pitch propellers, stressed-skin structure and flush riveting. The first one flew in 1935 and by the end of 1944 it accounted for over 90 % of the world’s commercial aircraft. It was considered by many to be virtually indestructible – not least due to the 500,000 rivets in its airframe. But by 1968 it was considered something of an anomaly for a commercial airline.

We took off over the city of Johannesburg, where we could see the mountains of yellow spoil from the gold mines, until we settled down over the Transvaal. It was early afternoon. As the plane was not pressurised our ears popped as we climbed to our cruising height of 10,000 feet. Below us was the endless veld. The vegetation was a uniform brown. It was the end of the dry season, and the heat was building up ahead of the rains. The plane bucked and bounced through the pockets of warm air. The engines roared as the pilot sought to keep the plane steady, causing some of the rivets on the wing to vibrate and from some of these on the engine cowl trickles of oil emerged. It is a picture that I can see as if it were yesterday - bucketing in a noisy sardine can 10,000 feet above the earth over the interminable and brown veldt.

Some two hours later we began to fly over the man-made forests of Pines and Eucalyptus (see here) that cover much of the western, high veld of Swaziland and over the irrigated fields of crops of the Middleveld until we touched down at Matsapha airport. It was around 4pm. The sun was hot. I walked to the airport building and quickly passed through immigration and customs to collect my case and start my new life. It was the 7th of September 1968, one day after Swaziland became independent. Waiting for me was the principal of the college, David Brewin, an old Africa hand and education specialist who had previously been in Tanzania. We climbed into his car. It was a metallic blue Ford Mustang convertible - not the 4x4 that I had expected - but it made more sense as we drove along the tar road to the college and later when I learnt that he was a confirmed bachelor. It took around 40 minutes to drive the 25 miles to the college, first along the highway towards the capital Mbabane and then turning left up through the Malkerns Valley. Irrigation had been introduced into the valley some years ago and much of the land was cropped. It became a little embarrassing as I asked him about the crops that we were passing: “What is that?” I asked again and again … to which the answer was variously citrus, pineapples, maize, sugar cane and rice – none of which I had seen before and about which I knew little. As we drove on it slowly dawned on me that here I was, at last, facing reality because I was the college’s new lecturer in crop production!